Why does America still use the Electoral College?

National Popular Vote Interstate Compact provides a viable alternative

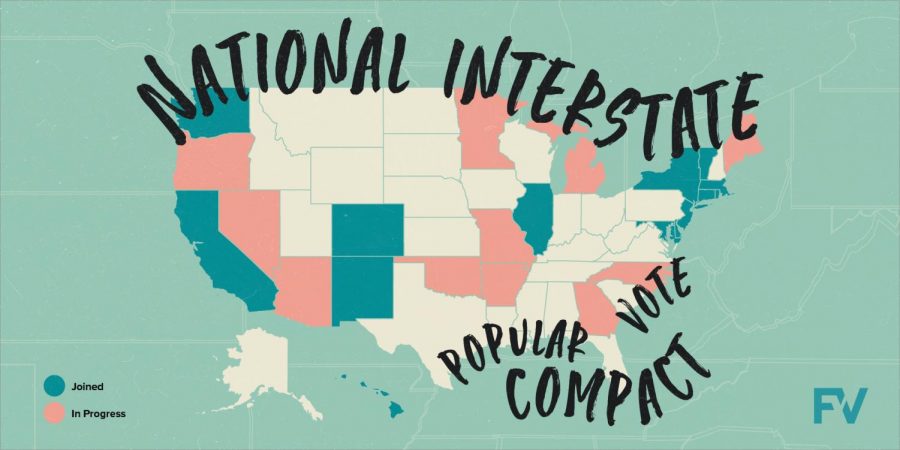

Graphic courtesy of FairVote.org

The National Popular Vote Interstate Compact is essentially an agreement between states in which they would pledge their electoral votes to the candidate that wins the most votes nationwide.

This story can also be viewed in our November 2020 Features Issue under the Print section of our website.

The Electoral College is America’s very own unique and almost unexplainable democratic lovechild.

But it seems odd that in the most powerful country in the world, a candidate can simultaneously win and lose an election.

In American history, there have been five instances in which a candidate has won the popular vote and lost the election: Andrew Jackson in 1824, Samuel Tilden in 1876, Grover Cleveland in 1888, Al Gore in 2000, and Hillary Clinton in 2016.

If the minority is allowed to dictate the winner in roughly 9 percent of presidential elections, why was such a system created in the first place?

“One of the biggest issues…was a travelling issue…an issue of just trying to get all the ballots in one place at a certain place in time,” AP Government and Politics teacher Brandon Andrews said. “There definitely is some Madisonian model ideas where you have the elite Renaissance-like founding fathers who didn’t necessarily trust the masses to be able to make the best decisions, and so they wanted to have some sort of filter that was put in place.”

While these areas of concern seem completely valid for their time period, they seem completely irrelevant in today’s society. Americans live in an incredibly interconnected world where travel is faster than ever and information travels at the speed of light. The general population is far more informed than those who lived to see the birth of this nation, and can judge for themselves which candidate best represents their interests.

So why hasn’t America gotten rid of this obsolete tradition?

Abolishing the electoral college would require an amendment to The Constitution, something that’s famously difficult to pass. An amendment requires a two-thirds approval in the House and Senate, and then a three-fourths approval by the states, a nearly impossible feat.

“Here’s the problem,” Andrews said. “If you’re a small state, why would you ever give up the electoral college?”

Because of the way it’s set up, the Electoral College allows states with smaller populations to get a proportionally more valuable vote than states with larger populations. For example, in Wyoming, the ratio of electoral votes to population is about .0000052, whereas in California it’s about .0000014. So essentially, a vote in California is worth nearly a quarter of a vote in Wyoming.

“It can make some people feel as though their vote doesn’t matter as much,” said senior Kimi Shirai, who is eligible to vote this election.

This also leads to some states being fundamentally more important than others in the electoral process.

“As it is, there are some states that are incredibly important, and I would argue too important,” Andrews said. “When [the election] only comes down to 10 states, then there’s definitely a problem.”

So, if an amendment is unrealistic, how does the nation address this issue? Enter the National Popular Vote Interstate Compact.

The National Popular Vote Interstate Compact is essentially an agreement between states in which they would pledge their electoral votes to the candidate that wins the most votes nationwide, according to an article on FairVote.org. But the Compact must obtain a majority (270) of the Electoral College votes before it can go into effect.

Such a resolution allows the popular vote to become the deciding factor in a presidential election without an amendment to the constitution, and remains constitutional because the Constitution itself gives states full control over how they allocate their electoral votes.

“To date, 15 states and [Washington], DC have passed legislation to enter the compact for a combined total of 196 electoral votes, meaning the compact is over 72.6 percent of the way to activation,” the FairVote article added.

California, which has the most Electoral College votes with 55, is among the 15 states that have passed legislation to join the compact. The legislation is also pending a vote in the state legislatures of Ohio, Pennsylvania, South Carolina, and Virginia according to an update by FairVote.org

There are, however, a lot of unanswered questions should this compact go into effect.

A question of the law’s constitutionality is always relevant when considering an agreement such as this. The Supreme Court could easily overturn such a resolution depending on the political makeup of the court.

Is such a law constitutional though? Proponents of the compact think so.

“The bill is a constitutionally conservative, state-based approach that preserves the Electoral College, state control of elections, and the power of the states to control how the President is elected,” according to the National Popular Vote website. “Under the current system, a voter has a direct voice in electing only the small number of presidential electors to which their state is entitled. Under NPV, every voter directly elects 270+ electors.”

With the passage of the National Popular Vote Interstate Compact, every vote will be equally represented, and, contrary to the current system, elections will become a national effort in which the outright majority will prevail.

Brady Horton is a senior at California High School. He’s attended Cal High all four years of high school, and has lived in San Ramon and Dublin his...