District proposing significant changes

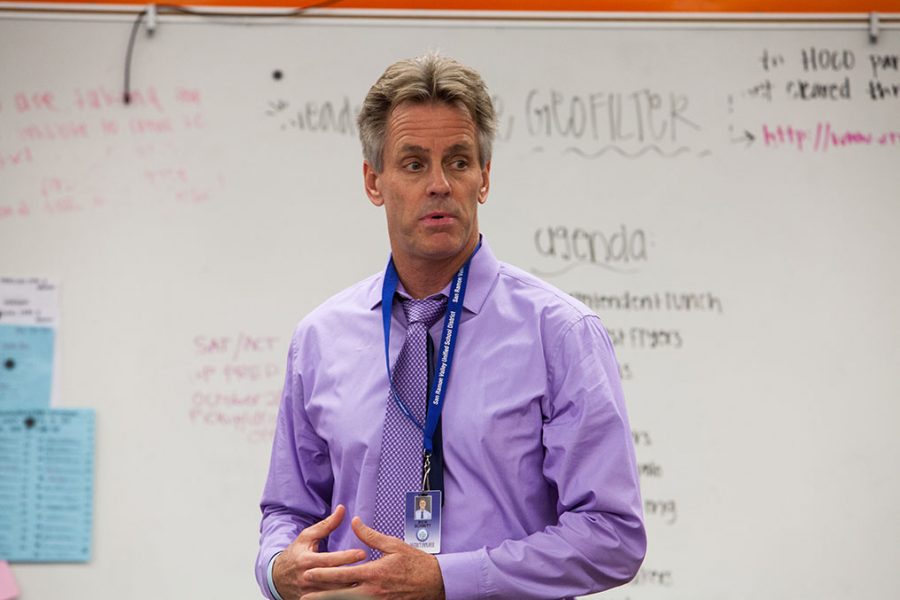

Superintendent Rick Schmitt’s vision for sweeping changes at Cal High and other secondary schools in the district, is so far being met with resistance from students, teachers and parents.

At an Oct. 24 meeting, the San Ramon Valley Unified School District Board of Education heard many parent and student concerns about Schmitt’s proposed plans, which are designed to combat student stress and deal with district funding problems.

Various issues have arisen during parent forums and student press conferences while Schmitt has promoted his 10-point plan.

Most of the outcry has been from parents, who are opposed to proposals that would prohibit high school students from taking seven classes on campus and reduce the number of elective classes required to graduate.

The negative response to the plans were due to the fact that many students either relied on or desired to take a seventh class in order to fulfill personal pursuits.

“People right now depend on the art classes offered at my school to fulfill their passions,” Cal senior Haley Horton told the school board. “Maybe they can’t afford art classes outside of school. Maybe their parents don’t support it. School may be the only place for them to be in their happy place.”

Such sentiments were shared by parents as well, including San Ramon Valley High parent Shelley Clark, who told the school board that both her children would have been unable to pursue their interests without a seventh period.

Because of this backlash from the community, Schmitt has since amended his plan to allow all currently enrolled high school students to still take a seventh period. It is not clear if the district will propose a six-class cap for future students.

Schmitt and the board members continue to emphasize that all of the proposals are still tentative.

“I don’t think anybody should feel necessarily that any of this is a done deal,” school board member Greg Marvel said at the meeting. “I would not support anything that cut arts, drama, or music and the fine arts in general.”

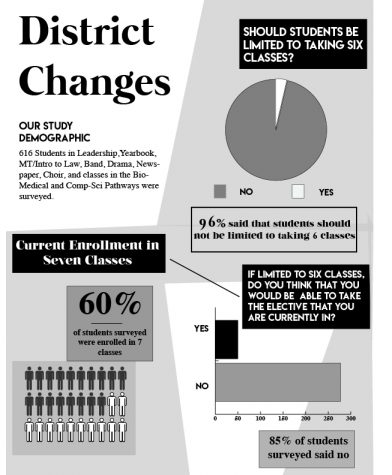

The Californian conducted a poll of 616 students in various elective courses including leadership, yearbook, choir, drama, mock trial, newspaper, band, and classes in the biomedical and computer science pathways.

Of these students, 590 or 96 percent believed that students should be allowed to take seven classes. About 60 percent of the students polled (366) indicated they are currently enrolled in seven classes. Surprisingly, 85 percent, or 308 of 366 students, said they don’t believe they would be able to take their chosen elective if the seventh period was eliminated.

The original plans were presented as a solution to student stress and improve student wellness, but many believe that the true objective is funding.

Clark and other parents asked for more transparency from the district regarding funding problems.

“If this particular initiative is about saving money, then let’s have a transparent conversation about that,” said Clark, whose comments were met with an ovation from the audience, many of whom marched with protest signs along Sycamore Valley Road to the meeting.

One of the signs displayed at the meeting read: “Continued Access to 7 on campus classes for incoming students!! Then it’s really about flexibility & options!”

Kelly Jellin, a parent of a Cal High student, sent a letter to Schmitt regarding what she believed to be the real reason behind the plan.

“Budgetary constraints are dictating the need to eliminate the 7th period,” Jellin wrote. “Please do not pretend that the primary reason for the elimination is for the students’ benefit. Many of the proposals seem to be… off loading the costs to parents.”

In an email Schmitt sent to parents on Oct. 18, he admitted that, as parents suspected, large parts of the plan’s priorities are a result of funding issues.

Schmitt explained in the email the funding challenges the district has faced since they began in 2013. He explained that the state of California changed the way it funds public schools from revenue limit to a system that prioritizes fundings for districts with higher economic needs.

“Because San Ramon Valley Unified School District has a much lower number of eligible students, we receive less state funding per student than most of our neighboring districts,” Schmitt wrote in his email.

Ann Katzburg, the president of the San Ramon Valley Education Association, said the costs associated with offering a seventh period at the four high schools has definitely jumped over the years. She said when a seventh period was created more than 20 years ago, about only 10 percent of high school students signed up for the additional class.

But as the district has become more competitive in recent years, Katzburg said that number has jumped to about 40 percent at most high schools, and as high as 50 percent of students at some schools.

Katzburg elaborated that the largest issue from the district’s standpoint is funding. Each school, based on enrollment, receives a student-to-teacher ratio of 27-to-one for five classes and is funded for those five classes.

This leads to an issue when students take six or seven classes, as their funding is distributed through the five classes, creating a student-to-teacher ratio of 38-to-one.

During the economic recession in 2008, tax money meant for schools was diverted to pay for other programs in the state of California. As the economy recovered, the state started a payback program to make up for the borrowed money. That payback process is set to end in the next two years, resulting in higher expenditures for the district, Katzburg said.

Classes at each school are determined by demand for certain subjects. As the school’s population grows, the 27-to-one ratio will be upheld, but reorganization of classes can putting some teachers into classes they weren’t hired to teach, Katzburg said.

Katzburg explained that as the demand for core classes increases, the optional elective classes will be condensed to allow for more classes in the core curriculum.

Schmitt’s claim that jobs will not be eliminated is true, but jobs could be reallocated and teachers moved. For example, an art teacher could be moved to English if more teachers were needed in that department.

As initially presented, Schmitt’s proposals were to increase options for students and staff, improve student wellness by decreasing student stress, and reduce class size without increasing costs to the district.

“… I believe that these ideas when they interact with each other will provide you and your family and ultimately many of your teachers more options,” Schmitt told The Californian editors and leadership students at an Oct. 11 press conference.

To accomplish this, Schmitt has proposed many changes in addition to reducing to six the maximum number of on-campus classes students can take.

He wants to reduce the number of classes required for graduation, provide more options for independent PE credit, offer more off-campus classes for credit, increase opportunities of internships for credit, reduce the number of Schoolloop notifications parents receive, and add a third start time so students could begin and end classes later in the day.

Schmitt’s proposals could impact various departments, specifically the arts, world language, and PE classes, which raises many concerns from teachers in those departments.

One of the proposed changes includes reducing the number of required classes for graduation from 24 to anywhere between 21 to 23.

Performing arts teacher Laura Woods is concerned that the reduction of electives will lead to a fewer classes offered in the art department. She believes this would cause funding issues for the arts overall as fewer classes would result in decreased donations, the main source of funding for art programs.

“What do employers want?” Woods said. “They want creative thinking, driven, empathetic, and well rounded individuals. The arts are what provide that.”

Woods also is concerned with higher level art classes because she thinks they could be eliminated altogether with this change. She said that as classes are eliminated, teachers’ jobs are in jeopardy because there won’t be enough classes to support them.

“The culture of the community will not change,” Woods said. “People moved to this community due to the options in school for the arts, to prepare for college, and to learn your passion.”

Another one of Schmitt’s ideas is the inclusion of Heritage schools, which allows students to take language classes, such as Tamil or Telugu, for those not offered on campus. He said such classes would lower the class sizes of the existing world language classes on-campus.

While first-year French teacher Miranda Kershaw supports the reduction of stress for students, the possible impact of the new proposals concerns her because she feels many students will drop electives in favor of required classes.

“In order for students to have space for elective classes the core requirements would have also need to be reduced,” said Kershaw.

But changes to the core requirements have not been proposed. Cal’s current graduation requirements allows for eight elective classes over the course of four years. But the proposed schedule would only allow for five or six elective classes in the same time period.

The district’s new policy, implemented this year, allows juniors and seniors who are on track to graduate on time to leave at lunch. As this is a popular alternative, teachers are concerned that students will opt out of electives in favor of leaving early, reducing class funding.

Class sizes are also a concern for 15 year PE teacher Lenard Matthews.

Matthews said this year the student cap for PE classes was increased from 50 students to 60, which is much more difficult for the teachers to manage and reduced the number of full-time PE teachers on campus.

Some PE teachers now have to work at two different schools due to the larger classes. That happened this year with longtime PE teacher and varsity football coach Eric Billeci, who now teaches part of his day at a middle school because he has only two PE classes at Cal.

Matthews is also concerned about having his job replaced by independent PE, which allows students who participate in either school team sports or individual sports to earn PE credits toward graduation.

“The problem we have with independent [PE] is we’re being told as professionals who are educated at teaching physical education that a coach of one sport is perfectly capable of doing what we do,” said Matthews. “Eventually it’ll lead to less jobs in physical education.”

While Schmitt’s ideas could impact PE and elective class teachers, many believe his plan will impact students the most. The Californian poll revealed that award-winning programs such as band, drama and yearbook could lose a staggeringly high percentage of students if limited to six classes.

Of the 106 band students polled, 90 of them said they took seven classes but only five of these students believed they would be able to take the class if limited to six classes.

“I believe that the administration is doing a disservice to the kids of Cal High and any other school they are affecting by taking away (a seventh) period,” yearbook editor in chief Turvi Sharma wrote in an email. “Not everyone’s main focus lies in the four core subjects but rather in an elective that they found their passion in or an art where they found their outlet.”

Joe Plechaty • Nov 8, 2017 at 10:50 am

If he wants to reduce stress on the students, how about doing something about what goes on in the Bathrooms at Cal High.