Box of bones discovered in Cal library

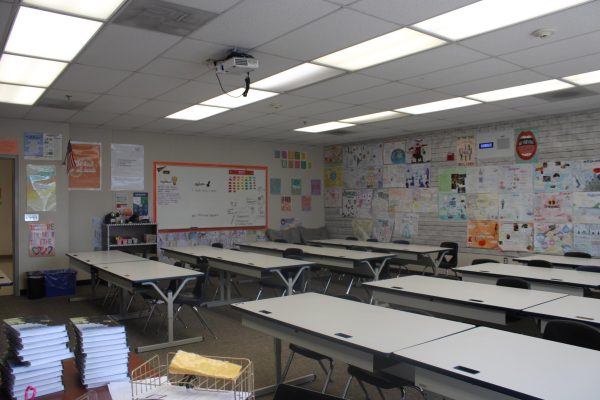

When new librarian Nikky Ogden decided to clean out part of the Cal High library in January, she never imagined she would be transported back to 1971, let alone taken back another 2,000 years.

“I was cleaning out one of the back cabinets of the library and found a box,” said Ogden recalling the event. “And I opened it up and there was a bunch of bones inside”.

An informational page found inside the box states that the bones were discovered in 1971 on the site of the present day gym during an excavation for earthquake analysis.

A newspaper clipping with pictures of the workers digging at the site was also found, but the reason for both being tucked away in the library remains unknown.

“We do have a ton of Cal High history stuff here in the library, so maybe they just thought it would be safe there for now,” Ogden said.

Ogden has contacted past librarians regarding the box of bones, but those who responded said they didn’t know anything about the bones ever being discovered, let alone stored in the library.

The only information Ogden found about these bone fragments is on an informational page inside the box, but the credibility is questionable.

The informational page reads,“Tests indicate that these bones date back to 150 B.C. and are possibly the remains of an Indian from the Yukots tribe which inhabited the San Ramon Area.”

One doubtful aspect is the unpopular spelling of the tribe’s name on the box. The name is most commonly and modernly spelled ‘Yokuts’.

The probability of a Yokuts’ remains found in this location is unlikely. According to the City of San Ramon website, the natives who inhabited the area south of today’s Norris Canyon Road in San Ramon and Dublin belonged to the Seunen tribe and inhabitants of the Alamo-Danville-San Ramon area were a part of the Tatcan tribe.

The Yokuts traditionally lived in the “San Joaquin Valley and the adjacent foothills of the Sierra Nevada in south-central California,” according to the Encyclopedia website.

This suggests that the individual of these remains would have had to travel to this San Ramon location specifically, or been brought there after his or her death.

A majority of the bones found also seem too small for a human, contradicting the idea that the informational page states.

One hollow fragment, judged to be a long bone such as a humerus or femur, and a bone assumed to be a piece of the cervical vertebrae of the spine are the only two pieces that resemble those of a human in size, observed science teacher Andrew White.

The other bones are more similar in size to those of an animal.

“The bones look like they might have been the product of a group of people devouring or prepping some kind of animal for food,” said White.

Science teacher Julie Bitnoff also speculates the animal jaw bone included in the box seems too clean to have been found with the others and it may be a fake.

But the discovery is still intriguing.

“It’s potentially very exciting, so it’s one of those things where we’re not one hundred percent positive,” Ogden said. “Things look like they’re probably legitimate but we just want to get confirmation before we put them on display.”

Cal High’s science department is unable to do so without a mass spectrometer, which can date artifacts and remains.The University of California Museum of Paleontology may be contacted to see if they can date the bones and either confirm or contradict the information provided on the box.

If the informational page is correct and these bones are from 150 B.C., they will be used in science classes to aid in lessons on evolution.

“You might be able to show, for example, if you can find what this animal was and compare it’s DNA sequence with an extant version of this animal if it’s still around then you can see how much of that genome has changed,” said White.

While the mystery of these bones still remains, the possibilites for their use are plentiful.

“I think it’s potentially very good for the school and could stir up some interest in our science programs,” said senior Kaelin Delaney.

Ogden also hopes to make the bones available for the whole school to see.

“It’s one of those things I think is definitely worth sharing with the entire school population,” said Ogden. “So I think keeping them in places where they are accessible to everyone, but still preserved and safe, is a good way to go.”